European and international regulation

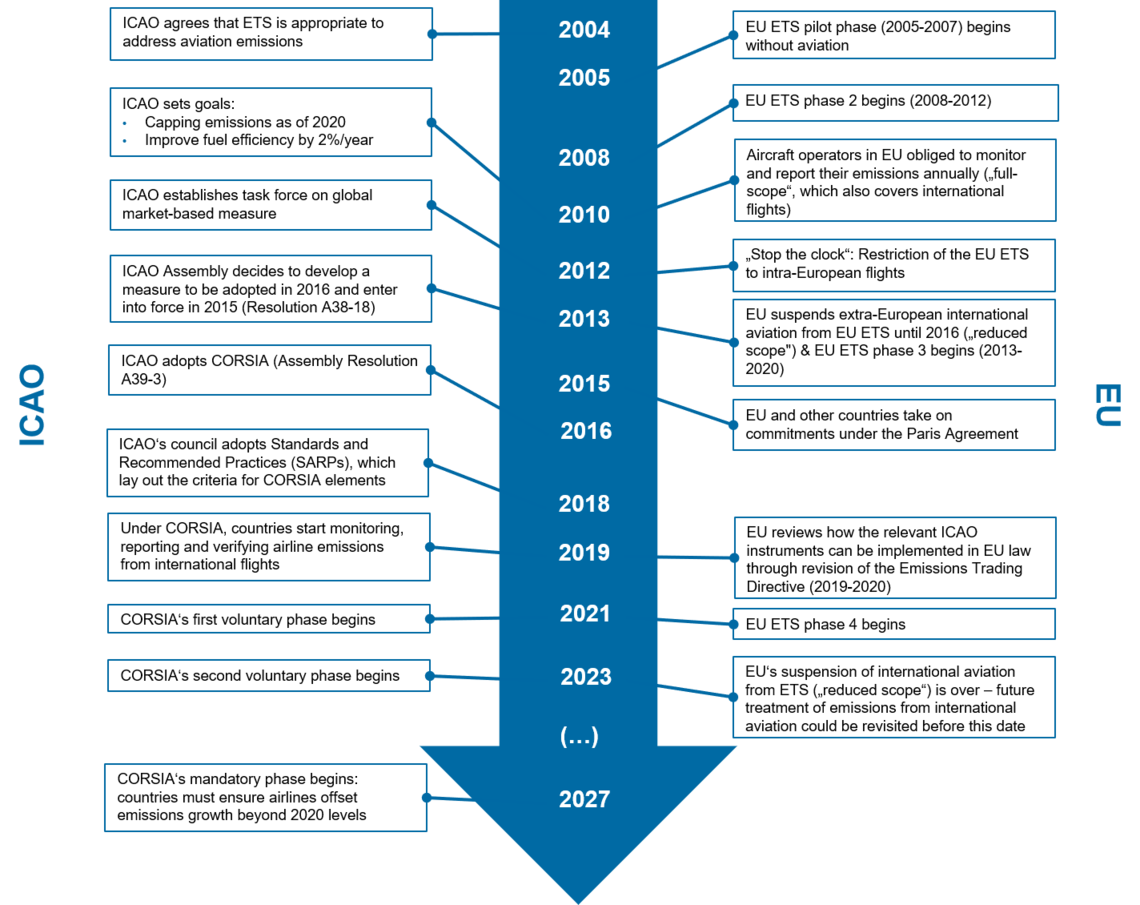

Aviation is addressed at the European level by the EU’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and at the international level by ICAO. Reporting under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change UNFCCC distinguishes between national and international aviation emissions. A regulation to reduce international emissions is difficult to implement as this requires a worldwide consensus. At the international level, it was decided in 2016 that a global market-based system should regulate aviation; the CORSIA instrument will come into effect from 2021.

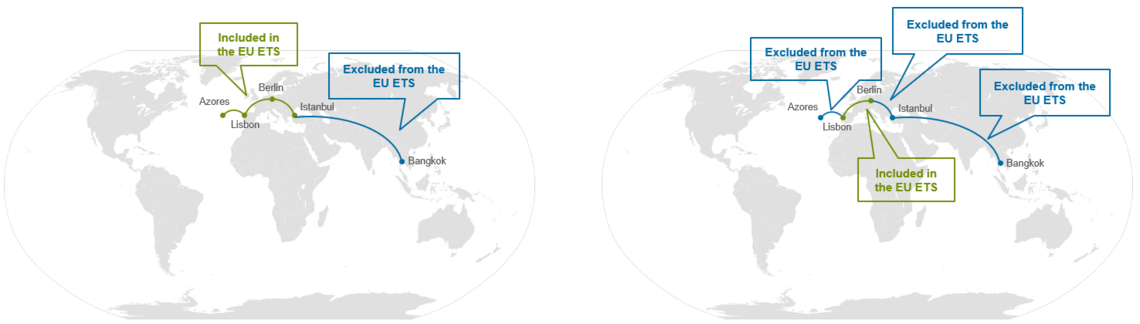

In addition, intra-European aviation has been covered by the EU ETS since 2012. The system regulates the emissions of intra-European flights via the trading of emission allowances. Up to 2021, air transport from EU to non-EU countries was therefore not covered by the ETS. The relationship between the EU ETS and the CORSIA system has not yet been clarified. A proposal from the European Commission is expected in the second quarter of 2021.

EU – emissions trading

Aviation in the EU is covered by the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). CO₂ emissions in aviation are therefore assigned a carbon price and their total volume is limited via the trading in emission allowances within the EU ETS. This instrument has not yet been able to achieve its full effect in practice. This is because, firstly, only some of the flights from the EU are covered by the ETS and, secondly, the prices for emission allowances are too low and the supply is too high for the EU ETS alone to be an effective instrument for more climate protection in aviation.

How is aviation covered by the EU ETS?

Aviation has been included in the EU’s Emissions Trading System since 2012. Prior to this, the EU ETS only covered stationary installations from the energy and industry sectors. Originally, all flights taking off and/or landing in European airports were to be included in the EU ETS (so-called “full-scope”). However, various countries – particularly the USA, China and Russia – viewed this as illegal taxation of airlines of countries outside the EU. Thus, the scope of the EU ETS was retroactively limited from the beginning and now only includes intra-European air traffic. Thus, the EU ETS covers only one third of the scope of air transport that was initially envisaged (see Figure 3‑1). The limited scope still applies. As soon as the exact design of CORSIA has been finalized, the scope of the EU ETS will be reviewed and either permanently reduced or returned to full scope.

All airlines operating flights that are subject to the ETS must monitor the emissions of these flights and report them to the EU by 1 April each year. Allowances equivalent to the emissions must be submitted by 1 May each year.

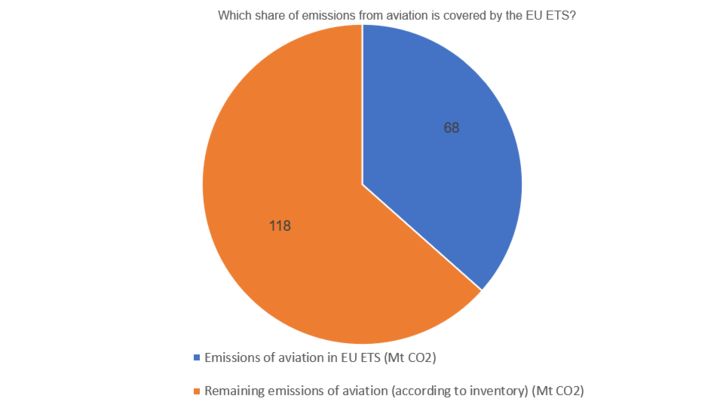

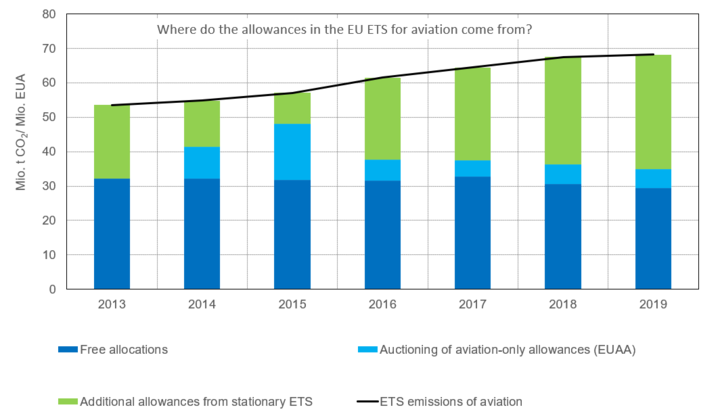

Currently, air operators receive a high proportion of these allowances free of charge. For emission levels above that, operators must purchase allowances at regularly scheduled auctions or directly from stationary installations covered by the EU ETS. In 2019, aviation emissions under the ETS totalled 68 million tons of CO₂ or nearly 40% of total aviation emissions. For the period of 2012 to 2020, airlines were allocated over 50% of the emission allowances they needed for free.

Between 2013 and 2020, the amount of allowances allocated free of charge to airline operators remained the same. From the start of the fourth trading period in 2021, they decrease by 2.2% per year (corresponding to the Linear Reduction Factor LRF).

Is the EU ETS an effective instrument for more climate protection in aviation?

The EU ETS was the first policy measure implemented to reduce emissions in the aviation sector. It thus had a pioneering function and sent an important signal in the right direction. However, as the EU ETS is currently designed, it does not have a strong impact in terms of increasing climate protection in aviation.

The reasons for this are:

-

Its limited scope:

As the EU ETS only covers intra-European flights, over 60% of aviation emissions are not currently covered by the GHG inventory.

Source: Oeko-Institut based on EEA (2019): Greenhouse gas data viewer. and EEA (2020). EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) data viewer. -

Only CO₂ emissions covered rather than all negative climate impacts

The EU ETS regulates only CO₂ emissions and not the indirect climate impact of flights. This simplification of the climate impact is particularly problematic in aviation. In addition to direct emissions from kerosene combustion, the gases emitted in high layers of the atmosphere lead to cloud formation and other chemical processes. According to current estimates, the GHG impacts of these effects are about one to three times higher than the CO₂ emissions generated by combustion.

-

Goal of overall EU ETS is too low

The EU ETS limits emissions by setting a so-called cap, i.e., an upper limit of the possible emissions, which the total amount of emissions in the system may not exceed. The cap is calculated roughly from the sum of the freely allocated emission allowances and the allowances (freely allocated or not) that are auctioned. For the period up to 2020, the cap is constant and constitutes 95% of the emissions from 2004 to 2006. Since that time, the emissions have increased significantly. For aviation, the cap is thus significantly lower than actual emissions. Operators must cover the gap between actual and permitted emissions by, for example, purchasing allowances from the stationary installations under the ETS.

Source: Oeko-Institut based on EEA (2020). EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) data viewer. However, if an aviation operator purchases allowances from an industrial installation, it does not mean that emissions are actually mitigated.

The surplus of allowances is currently so high that the allowances needed by aviation have no effect on the overall ETS.

There is a substantial surplus of allowances in the stationary EU ETS; in 2019 this surplus amounted to over 1000 million European Union Allowances EUAs. Aviation’s demand for approximately 30 million allowances from stationary installations is not significant enough in the current oversupply of allowances that it leads to a mitigation of emissions elsewhere. This situation could change in the future if the EU ETS is reformed. So far, it has been decided that a so-called market stability reserve is introduced to reduce the surplus of allowances. In addition, allowances are to be completely cancelled and the cap for the entire EU ETS is to decrease from 2021 onwards.

The prices for emission allowances under the EU ETS are too low to make progress with the decarbonization of aviation.

Only in 2018 did carbon prices in the EU ETS exceeded the limit of €10 per ton of CO₂. By mid-2020, these prices were €30 per ton; they are expected to rise further by 2030. Therefore, only low additional costs arise for aviation operators that purchase allowances to offset their emissions that exceed the cap. Thus, the EU ETS currently offers no incentive to reduce emissions, for example by using aircraft with lower emissions. This is because purchasing allowances is much cheaper than implementing such measures. At the moment, a flight from Berlin to Mallorca is about €3 more expensive if the cost of the allowances is added to the ticket price (with emissions of 0.27 tons of CO₂ per passenger according to Atmosfair calculations, a certificate price of €20 per ton of CO₂ and free allocation of certificates amounting to 43%).

-

Uncertain climate footprint of “sustainable fuels”:

One option for more sustainable air transport is the use of synthetically produced fuels. In the EU ETS, fuels from renewable sources are in principle assessed as zero emissions if they meet certain criteria in terms of sustainability and mitigated emissions. These follow the criteria of the Renewable Energy Directive (2018/2001) in Articles 25(2), 29(20), 26(1) and 29 (2-7). However, the level of emissions generated by the production of “sustainable aviation fuels” is uncertain for some processes. At present and for the foreseeable future, the prices for emission allowances are significantly lower than the costs for synthetic fuels – so they cannot currently make a significant contribution to more climate protection in aviation.

How could aviation be regulated more effectively under the EU ETS?

The idea of the EU ETS is to limit the total emissions of the system and thus to stimulate trading of allowances between market participants so that emissions are reduced where the costs of doing so are lowest. However, the complex system needs further adjustments to generate sufficient incentive effects. Currently, there are two windows of opportunity to reform the EU ETS and make it more effective. Firstly, the EU ETS needs to be adjusted in the context of the international CORSIA system. Secondly, increases in the EU’s climate targets for 2030 are planned, to which the EU ETS will contribute significantly.

The most important options for reforming the EU ETS with a view to aviation are:

-

Adjustment of the emissions cap:

The decisive factor is the level of the cap, i.e. the total quantity of emissions permitted within the system. As experience gathered in the first years of the EU ETS has shown, a static cap is not enough. It cannot take into account actual developments such as a decrease in emissions due to economic or health crises or faster technological developments such as the use of renewable energies. Adjustments to the cap can involve the absolute level of emissions and the speed of emission reductions. The speed at which the cap is reduced is determined by the Linear Reduction Factor LRF. It has already been decided that the LRF will increase from 1.74% to 2.2% in the fourth trading period starting in 2021. In contrast to previous years, the cap for air transport also decreases annually in parallel with that of the stationary sector. The overall cap must be adjusted in view of the substantial surplus of allowances, the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, which is expected to lead to a collapse in allowance demand, and the long-term European climate targets that have been set. According to calculations carried out by Oeko-Institut, the cap should be reduced by 205 million Annual Emission Allowances (AEA) and the LRF should be increased to up to 5.07% (these calculations were made before the Covid-19 pandemic and thus do not include the significant decrease in aviation emissions and other ETS emissions).

-

Reduction of free allocation of emission allowances:

Allowances are allocated for free under the EU ETS to avoid carbon leakage, i.e. the migration of activity harmful to the climate to another country or the shifting of CO₂ emissions outside the economic area. In the case of aviation, leakage is unlikely – especially for passenger transport: no one will fly from Berlin to Mallorca via Ukraine to stay outside the scope of the EU ETS. It would therefore make sense to abolish free allocation for aviation. This would directly result in higher costs and incentives to reduce emissions.

-

Additional measures:

-

Numerous additional measures that are currently being discussed for stationary installations under the EU ETS could also be applied to the aviation covered by the system. These would generally lead to an increase in costs or to a stabilization of prices (e.g. carbon floor price).

-

It makes sense to continue to separate stationary installations and aviation under the EU ETS. This will allow the quantity of allowances available for aviation to be more precisely controlled.

-

Connecting the EU ETS with other emission trading schemes would increase the system’s geographic coverage and its effectiveness, especially as regards aviation. Currently, flights are not covered by the EU ETS if they depart from or arrive at airports outside the European Economic Area. By linking emission trading schemes that include aviation, more flights can be included in the system. It has already been decided that the emissions trading systems of Germany and Switzerland will be linked, but the practical implementation of this has been postponed because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

-

CORSIA system under the ICAO

What is CORSIA?

The Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) is a new global climate protection instrument for international flights. Adopted by the International Civil Aviation Organization ICAO of the United Nations in 2016, it aims to offset the increase in CO₂ emissions after 2020. The system obliges aircraft operators either to limit their CO₂ emissions, for example by using more efficient aircraft or so-called “sustainable aviation fuels” or to buy carbon offset credits from climate protection projects.

How did CORSIA come about?

In the negotiations that led to the Kyoto Protocol of 1997, the countries could not agree to which country the CO₂ emissions from international flights should be ascribed. Should they be attributed to the country in which kerosene is refuelled or to the country in which the plane takes off or lands? Or should they be allocated according to the nationality of the passengers? It was ultimately decided that international flights would be excluded from the countries’ climate targets altogether. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) was tasked with taking measures to limit these emissions.

The ICAO negotiations initially stalled for many years. In 2008, the EU lost its patience and decided unilaterally to regulate the CO₂ emissions of international flights and include these in its Emissions Trading System from 2012. Many countries objected to this, arguing that the EU was improperly regulating their airspace. A substantial conflict and a trade war threatened. The EU then limited its unilateral regulation to domestic flights on the condition that an agreement was reached under the ICAO. This gave impetus to the negotiations. In 2016, the International Civil Aviation Organization finally adopted CORSIA.

How does CORSIA work?

In recent decades, CO₂ emissions from international flights have risen steadily. While emissions per passenger have decreased due to aircrafts being increasingly fuel-efficient, the volume of passengers has grown much faster. CORSIA aims to address this trend by allowing air transport to continue to grow and holding actual CO₂ emissions at 2020 levels through mitigation measures and offsets. Airlines can meet their commitments in three ways:

-

Less kerosene consumption: The kerosene consumption can be reduced by, for example, using fuel-efficient aircraft. Among other things, airlines can use more efficient aircraft and thereby decrease kerosene consumption.

-

Sustainable aviation fuels: So-called sustainable aviation fuels can lead to lower greenhouse gas emissions. These include biofuels produced from renewable raw materials, synthetic fuels that obtain carbon in kerosene, for example by capturing CO₂ from the air, and fossil fuels that result in lower greenhouse gas emissions during their production.

-

Offsetting: Here, the remaining CO₂ emissions above the 2020 levels are offset by the purchase of offset credits. Offset projects such as solar installations or reforestation are intended to reduce the same amount of greenhouse gases elsewhere.

It is expected that airlines will primarily use offsetting as this will be the most cost-effective option in the short term.

CORSIA will initially operate from 2021 to 2035. Participation is voluntary until the end of 2026: during this period, CORSIA will only take effect for flights between countries that voluntarily participate. As of 30 June 2020, this includes 88 countries, covering approximately 77% of international flight activity. Of the largest contracting parties, the EU, the U.S. and Japan have participated from the start; China, India and Russia, however, have not. From 2027, participation will be mandatory for most countries with the exception of very poor countries and those without maritime access.

How effective is CORSIA for the climate?

CORSIA is likely to have only a very small climate impact. There are several reasons for this:

-

Limited to CO₂ emissions: CORSIA only regulates CO₂ emissions and not the indirect climate impacts of flights which, according to previous estimates, could be between the same and three times higher than these CO₂ emissions.

-

Ambition of target: CORSIA only aims at limiting or offsetting the increase of emissions above 2020 levels. However, to meet the climate goals of the Paris Agreement, emissions from all sectors must rapidly decrease.

-

Quality of carbon offsets: In the case of offsetting through climate protection projects, it is often uncertain whether the offset credit means that one ton of CO₂ has actually been reduced. In the case of CORSIA, two aspects are particularly problematic. Firstly, in the first phase from 2021 to 2023, only offsets from old projects can be used. This will hardly result in climate protection. Secondly, the requirements for forest projects are particularly questionable because it needs to be guaranteed that the forest will exist for only 20 years.

-

Risk of double counting: When using carbon offsets, there is a risk that both the airline and the country in which the climate protection project is implemented count the same CO₂ mitigation towards their targets. CORSIA therefore requires programs that issue carbon offsets to avoid this type of double counting. To date, however, there are no international rules under the Paris Agreement to ensure this.

-

Carbon footprint of “sustainable aviation fuels”: Some of the production of these aviation fuels involves significant greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, there are some significant uncertainties in estimating these emissions.

-

Only international flights are included: CORSIA addresses only the emissions of international flights. This means that the domestic flights of the countries are still not addressed by mitigation measures. Flights within the European Economic Area are covered by the EU ETS, both national flights and flights between the countries of the European Economic Area. An appropriate linking of the EU ETS and CORSIA should ensure that mitigation measures address all aviation emissions.

-

Changing the baseline in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic:

It was originally envisaged that average emissions in 2019 and 2020 would be used as the baseline for CORSIA so that emissions growth above these levels would have to be offset by airlines from 2021 onwards. In response to the collapse in air travel in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, ICAO decided in late June 2020 that only the emission levels of 2019 would be used as the baseline for CORSIA. Since emissions are expected to remain below 2019 levels for a few years after 2020, there will be no emissions growth to offset during the pilot phase of CORSIA. As a consequence, this means a 25% to 75% reduction in the mitigation effect of CORSIA, depending on how quickly air travel returns to pre-pandemic levels.

Links

EU ETS

-

ETC/CME (2019): Trends and projections in the EU ETS in 2019

-

EEA (2019): EEA greenhouse gas data viewer

-

EEA (2020): EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) data viewer

-

Oeko-Institut e.V. (2019): The role of the EU ETS in increasing the EU’s climate ambition, Assessment of policy options.

CORSIA

-

ICAO (2020): What is CORSIA and how does it work?

-

T&E (2019): Why ICAO and CORSIA cannot deliver on climate

-

Oeko-Institut (2020): Should CORSIA be changed due to the COVID-19 crisis?

-

Oeko-Institut, CE Delft, TAKS (2020): Further development of the EU ETS for aviation against the background of the introduction of a global market-based measure by ICAO.